Life of the Mind

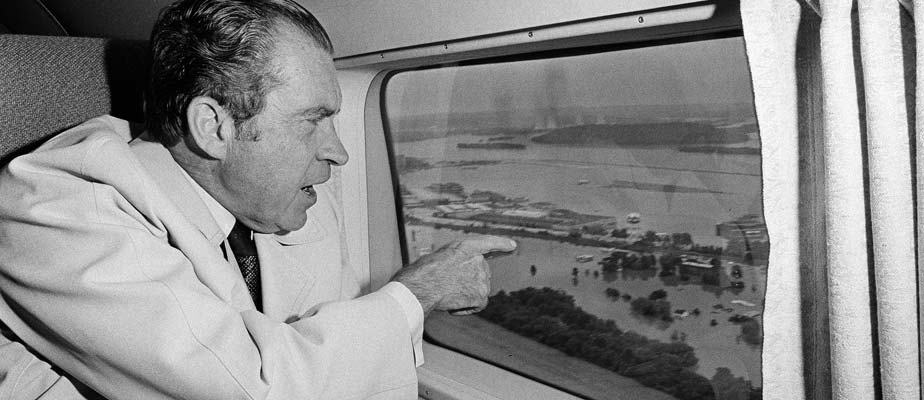

President Richard Nixon studies the flood damage in the aftermath of Hurricane Agnes, near Harrisburg, Penn., from his helicopter window, June 24, 1972.

Lessons in Disaster

Historic Hurricane Agnes and its effect on government disaster policy

by Timothy Kneeland

Disasters in the form of blizzards, earthquakes, floods, ice storms, hurricanes, snowstorms, tsunamis, tornadoes, and wildfires have been a constant hazard to life and limb in the United States. However, only since the mid-20th century has the federal government played a permanent role in dealing with disasters and their aftermath.

As a professor of political science, I use the study of natural disasters to teach important lessons about the nature of government, policy-making, and American culture. Students study how disaster went from being considered “acts of God” and personal misfortune in the 19th century to our current expectation that disasters should be controlled, mitigated, or responded to by the government. Students also learn that floods are less likely the result of nature and more likely a result of government sponsored and supported development on flood plains. Hurricane Katrina serves to highlight and expose social problems in America that center around race and class. Finally, students learn that under the Constitution, disasters are ultimately the responsibility of state and local governments and that federal action before, during, and after a disaster must be at the invitation of state authorities. Students also study how elected officials view disasters as political issues and not merely policy issues.

In addition to teaching about disasters, I do research on natural disasters and recently completed a book-length study of how Hurricane Agnes in 1972 shaped Richard Nixon’s disaster policy. My hope is that a historical study of this pivotal moment in federal disaster policy will provide lessons for the present that can be translated into more effective disaster policies at every level of government. The study will also provide context for our current disaster policies that will reveal long-term deficiencies in the disaster safety net.

There are some interesting parallels between Hurricane Agnes and more recent disasters such as Hurricane Sandy. Agnes struck the eastern seaboard of the United States in late June 1972. The storm combined with another weather front out of the Ohio Valley, and together the two storms dumped billions of gallons of water over Pennsylvania and New York. Towns and cities across those states suffered floods of epic proportion and destructiveness. The hardest hit were Corning and Elmira in New York and Wilkes-Barre in Pennsylvania, with these cities witnessing water upwards of ten feet covering their downtowns. The flooding left tens of thousands of people homeless, caused property damage in excess of three billion dollars, and left 122 people dead.

Following the initial disaster, those living in the afflicted cities dealt with dozens of government agencies involved in disaster response. These agencies were often understaffed, ill prepared, or at odds with one another. Officials working for the federal government did not always communicate effectively with officials at the state level.

Disaster survivors who had applied for temporary housing and government-issued trailers were still without them six weeks after the storm. Although Hurricane Agnes was front-page news, the media and public eventually began to pay attention to other events, which left people in the devastated cities and towns feeling abandoned. To raise awareness and money for those who suffered from the Agnes flooding, comedian Bob Hope hosted a star-studded telethon in late July 1972. For a few weeks thereafter Agnes remained in the press, but by that fall the public had largely forgotten about people in the flood zones.

In the long term, many people in Corning, Elmira, and Wilkes-Barre found themselves saddled with burdensome debt as a result of Agnes. The National Flood Insurance Program was relatively new in 1972; most people had not opted in to this program prior to the flood, which left them uninsured. The residents of the afflicted cities were offered low interest government loans so they could rebuild, but some found themselves bearing two mortgages, while others—who had already paid off their homes—spent the remaining years of their lives paying off their new mortgage.

Victims of Hurricane Sandy might be heartened to learn that following Agnes many local communities created citizens groups that lobbied on behalf of the residents to state and federal legislators and agencies. These pressure groups led elected officials to advocate for improving governmental response to disaster, including a call for more subsidized insurance to provide post-disaster aid, a centralized disaster agency to eliminate fragmentation among agencies, and better warning and mitigation systems that would prevent or minimize future flooding. In turn, the Nixon administration responded by expanding the National Flood Insurance Program and making mitigation of disaster the cornerstone of the Disaster Relief Act of 1974.

Students of natural disaster know that policy rarely changes after a singular event such as a hurricane or flood. Disaster policy has changed more often as a result of incremental changes over time. Thus, despite the call for a central disaster agency in 1972, it was to be another seven more years of disasters, both natural and human, before Jimmy Carter created the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) in 1979.

In the end, we can anticipate that despite the best of intentions we shall continue to see a need for an evolving government policy on disasters that continues to focus on mitigation but also responds more equitably and efficiently to the needs of those who are victimized by disasters.

Timothy Kneeland, Ph.D., is a professor of history and director of the Center for Public History at Nazareth.