Connections

Spring-Summer 2021

On Break, In Service

The alternative break program links communities and cultures, teaching advocacy and encouraging action. READ »

Composing the Story

As industry demand for digital media scoring increases, so does interest among music composition students. READ »

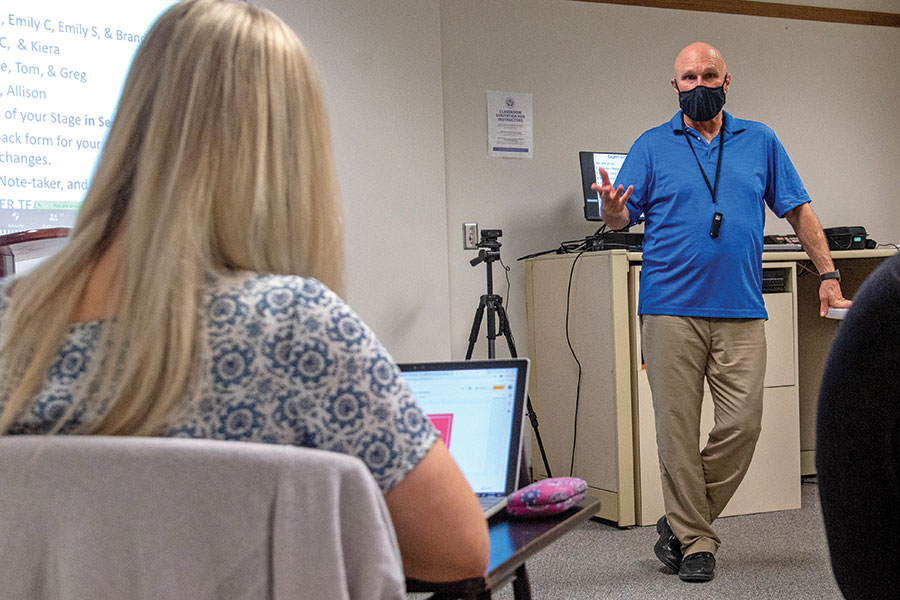

Honing Our Craft

Collaboration yields the best outcomes when it comes to improving teaching strategies. READ »

Pouring it Forward

Physical therapy students are among the first to use new high-tech equipment that has valuable implications for stroke patients. READ »

10 Questions

Getting to know social worker Serena Viktor ‘20, ‘21G and music therapist Kaylee Gray ‘21. READ »

Challenge the Status Quo

Chris Hilderbrant seeks to effect change through action, at work and in his personal life. READ »

Service Above Self

Meaghan de Chateauvieux reflects on the elements of her Nazareth experience that she continues to call on now. READ »

Good Work for a Good World

Gavin Thomas leads with a deep commitment to making a positive difference. READ »