Lessons Learned: Comparing 1918 Flu Pandemic to 2020 COVID-19

By Timothy Kneeland

The COVID-19 pandemic has altered the social patterns and work habits for most Americans, and although the situation is unusual in its scale, it is not unprecedented. I've been teaching a class and writing about natural disasters for over a decade. One of the events we study is the 1918 influenza pandemic, which killed over 675,000 Americans and 50 million to 100 million people worldwide.

St. Louis Red Cross Motor Corps on duty October 1918 during the influenza epidemic. (Library of Congress)

Much like COVID-19, the novel coronavirus that began in China in 2019, the 1918 influenza pandemic started with a disease that mimicked the ordinary flu but with deadlier results, killing not just the elderly, the very young, or those already ill but killing many young and healthy individuals in their 20s and early 30s. The 1918 disease baffled doctors who thought a bacteria might cause it and who rushed to produce an anti-bacterial vaccination, which proved ineffective against the virus. Their misguided approach was because virology was in its infancy, and science lacked the sophisticated electron microscopes that now allow us to see submicroscopic viruses.

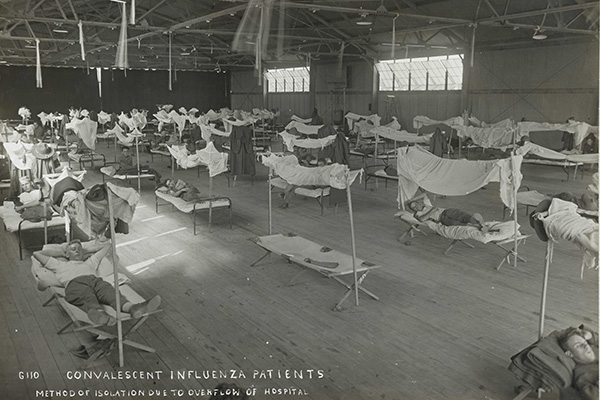

U.S. soldiers in Arkansas convalescing in 1918. (National Archives)

Exacerbating the situation in 1918 was the fact that the United States was fighting World War I, and the federal government, led by Woodrow Wilson, ignored the disease to focus on winning the war. This left state and local governments to combat the mysterious illness by themselves. And it was through their trial and error that we learned the effective strategies for dealing with pandemics, such as surveillance to track the spread of the disease, social distancing by closing down places where people gather, and quarantining entire cities to prevent the disease from arriving in an area. Studies by historians such as Alfred Crosby and the writer John Barry show that rigorously instituting such practices saved countless lives.

In 2020, we have applied the lessons of 1918 as a means of "flattening the curve" to slow the spread of the illness and give us the time to develop an effective antiviral treatment and create a vaccine to reduce the risk of getting and spreading the virus. In many ways, we are in better shape than our forebears. We may have been slow to respond, but now all levels of government are engaged in combating this illness. Emergency medicine, virology, and public health are all robust aspects of science we can employ to assist us. Knowledge about the disease is clear and widespread. However, all of our best intentions will not work if people do not follow the rules of social distancing, so please do your part and make the sacrifice of not hanging out with large groups of friends until the crisis is over.

Our efforts at social distancing have come with a cost that is pushing our economy into recession. There was less of an economic disruption during the 1918 pandemic because the war effort was providing a stimulus to the economy. In 2020, industry after industry has curtailed its business and furloughed or laid off workers.

This looming economic disaster leads me to another lesson — from our experiences in 1918 but from my just-published book Playing Politics with Natural Disaster: Hurricane Agnes, the 1972 Election, and the Origins of FEMA: Disasters fall heaviest on the most vulnerable populations. As I write this, the government is preparing a disaster relief package that is aimed at stimulating the economy. Too often, disaster relief provides "disaster capitalism," a bailout of the wealthiest corporations such as the airline industry, while neglecting the many individuals who have suffered severe economic loss. Many of those furloughed or laid off are students, one-income families, and people working multiple part-time jobs to make ends meet. The government must also clearly address the needs of those whose precarious economic circumstances have been worsened by our attempt to stave off the spread of COVID-19.

A final lesson I would urge upon you, is not to allow the blame game or political finger-pointing to cloud the issue that at all levels of government — from local, to state, to federal — we were unprepared for this pandemic. We lack respirators, we lack masks, we lack testing equipment, and, until recently, testing sites. Mitigation and prevention are clearly the best means of dealing with disasters, but are the least likely to be deployed. Some of this is because the public responds to emergencies by reelecting politicians who provide generous benefits after a disaster — while the public rarely showers votes on those who spend taxpayer dollars on prevention and mitigation. After the initial COVID-19 crisis is past, there will be hearings, investigations, and reports, as there should be, but we need to act on the conclusions so that the next disaster does not catch our government and its people off guard.

As you read this, please know that you are not alone; we are in this together. We can all do things to ease this crisis by following the practices of social distancing, not spreading disinformation, and by being patient with one another, being kind to those around you, and being generous with those who are in need.

Praise for Prof. Kneeland's latest book

Playing Politics with Natural Disaster (2020)

"This outstanding book shows that debates over the nature of disaster relief and the role of the federal government are not new. Timothy W. Kneeland's painstaking retelling of the effects of Hurricane Agnes is a significant contribution to understanding how disasters can yield policy changes."

— Thomas Birkland, North Carolina State University, author of After Disaster and Lessons of Disaster

Expert Perspective

Timothy Kneeland was featured for his research on what we can learn about COVID-19 by studying the 1918 influenza pandemic:

- On WXXI Connections March 24, 2020. Listen to the recording >

- On this TV News Channel 8 video news story >