PHL/LST 375: The Liberal Arts

Commentary by Marjorie Roth, December 2013

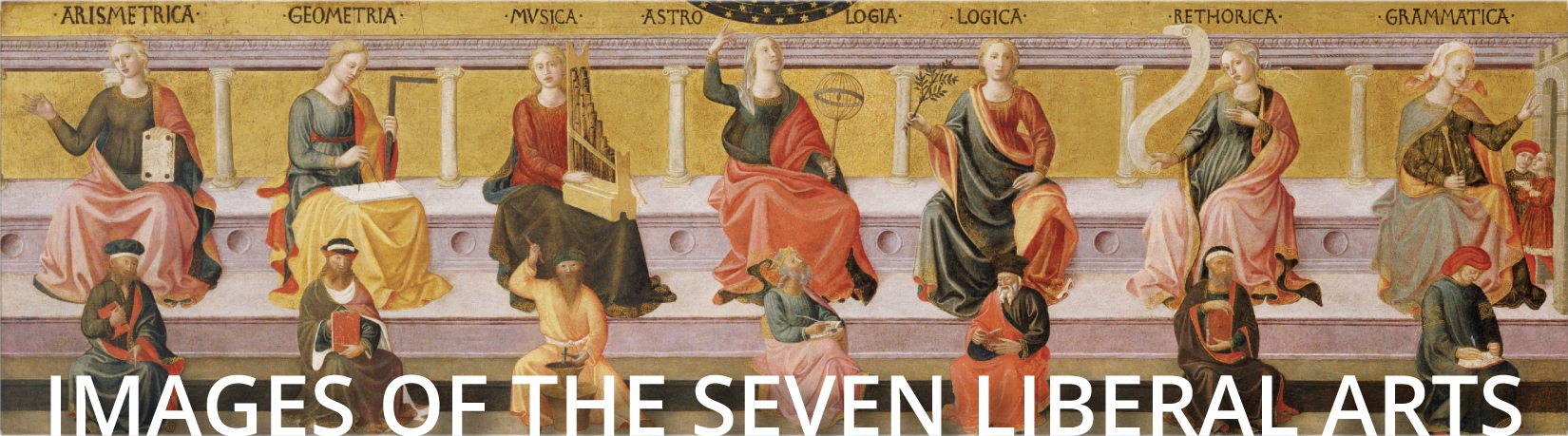

The Hortus deliciarum (Garden of Delights) is an illuminated encyclopedia compiled during the later 12th century by Herrad von Landsberg, abbess of the Hohenburg Abbey in Alsace. A compendium of medieval knowledge designed to instruct novices, Herrad’s Hortus includes an image of the seven Liberal Arts dispersed gracefully in a “rose window” pattern around the allegorical figure of Lady Philosophy, beneath whom are two of her most famous practitioners (Socrates and Plato). The three heads embedded in her crown represent ethics, logic, and physics, the three main branches of philosophical study at the time. The strong medieval connection between philosophy and theology is made clear in the banner Philosophy holds, which reads: “All wisdom comes from God; only the wise can achieve what they desire.”

Seven streams flow from the inner circle to the outer ring of the illustration where the seven Liberal Arts reside, each with a characteristic attribute and a descriptive phrase in the arc over her image: Grammar (book & whip/“Through me all can learn what are the words, the syllables, and the letters”); Rhetoric (tablet and stylus/“Thanks to me, proud speaker, your speeches will be able to take strength”); Dialectic (dog’s head & hooked hand/“My arguments are followed with speed, just like the dog’s barking”); Music (harp, kithara, & harmonium/“I teach my art using a variety of instruments”); Arithmetic (beaded cord for counting/“I base myself on the numbers and show the proportions between them); Geometry (compass & staff/“It is with exactness that I survey the ground”); Astronomy (stars & magnifying tool/“I hold the names of the celestial bodies and predict the future”).

Seated outside and below the larger circle are four men—poets or magicians—said to be producing fictional tales, poetry, or perhaps even magic spells. In Herrad’s opinion, such things lie outside the higher philosophical and theological goals of the Liberal Arts and must therefore be inspired by impure spirits (symbolized by the black birds perched on the shoulders of each man).

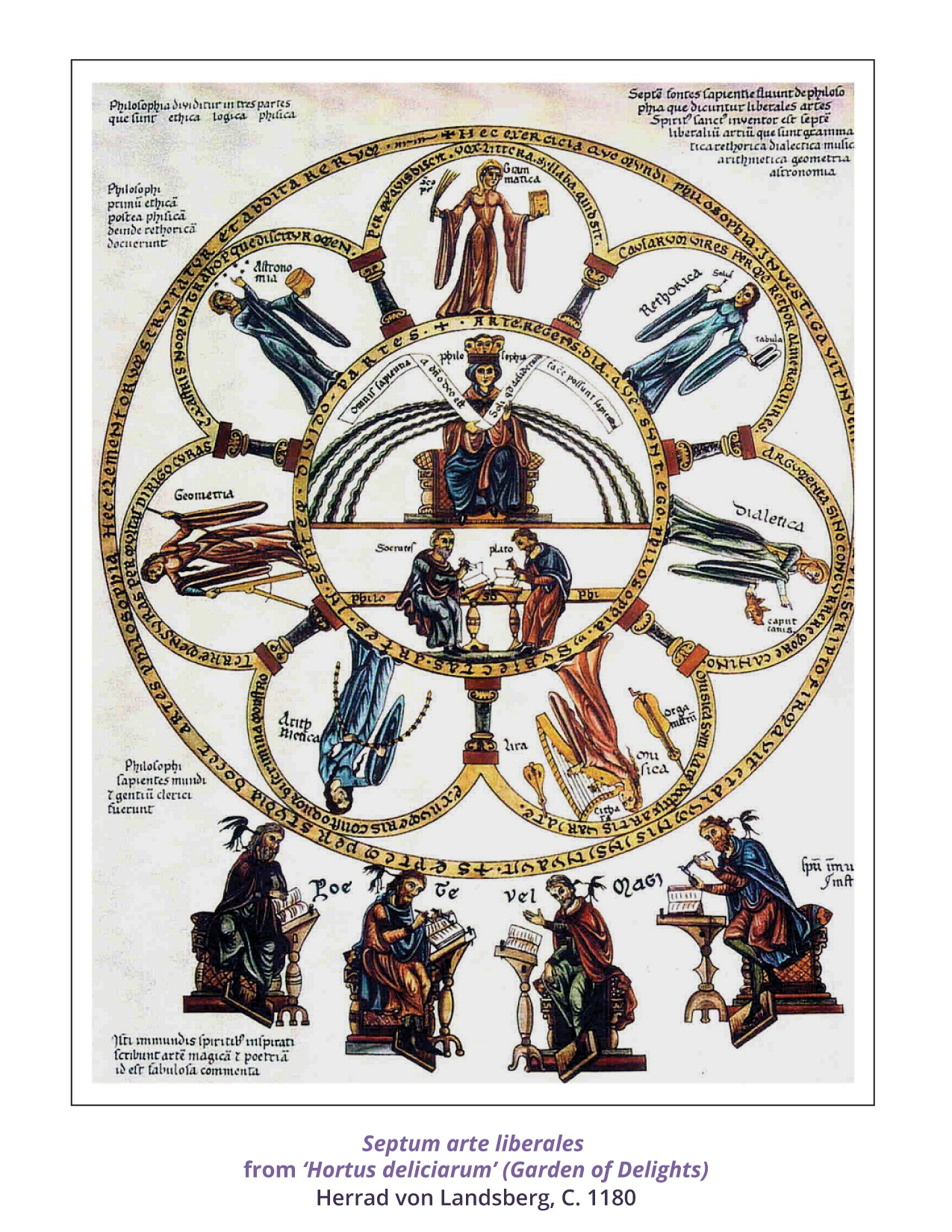

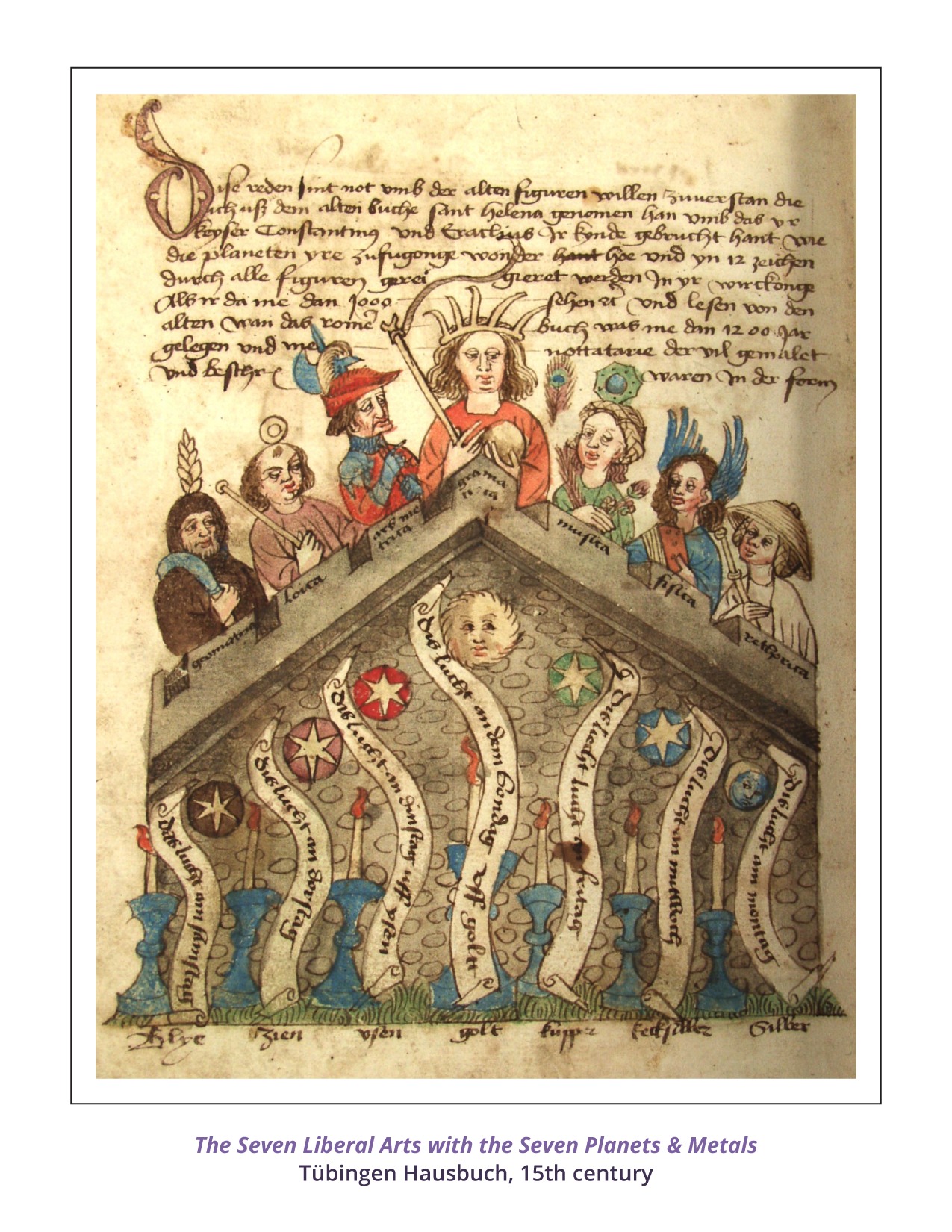

Ancient Roman philosopher Anicius Manlius Severinus Boethius (d. 524 AD) is known for writing the Consolation of Philosophy while he was unjustly imprisoned for treason near the end of his life. In this famous text, the allegorical figure of Philosophy visits Boethius and teaches him how to ease his suffering through contemplation of the good. According to Philosophy, the seven Liberal Arts are the necessary preparation for philosophical study. In this beautiful illumination from a 15th century French manuscript copy of the Consolation, we see Lady Philosophy introducing the seven Liberal Arts to Boethius, who is standing on the far left of the image. The ladies’ costumes represent the height of late medieval French fashion. Philosophy’s hennin is particularly elaborate, being draped with what look like loose page gatherings from a manuscript. Each of the Arts carries an appropriate attribute: Grammar (book); Rhetoric (scroll); Logic (patterned wheel representing logical patterns of argument); Music (musical notation); Geometry (square & measure); Arithmetic (scroll with symbols); Astronomy (armillary sphere).

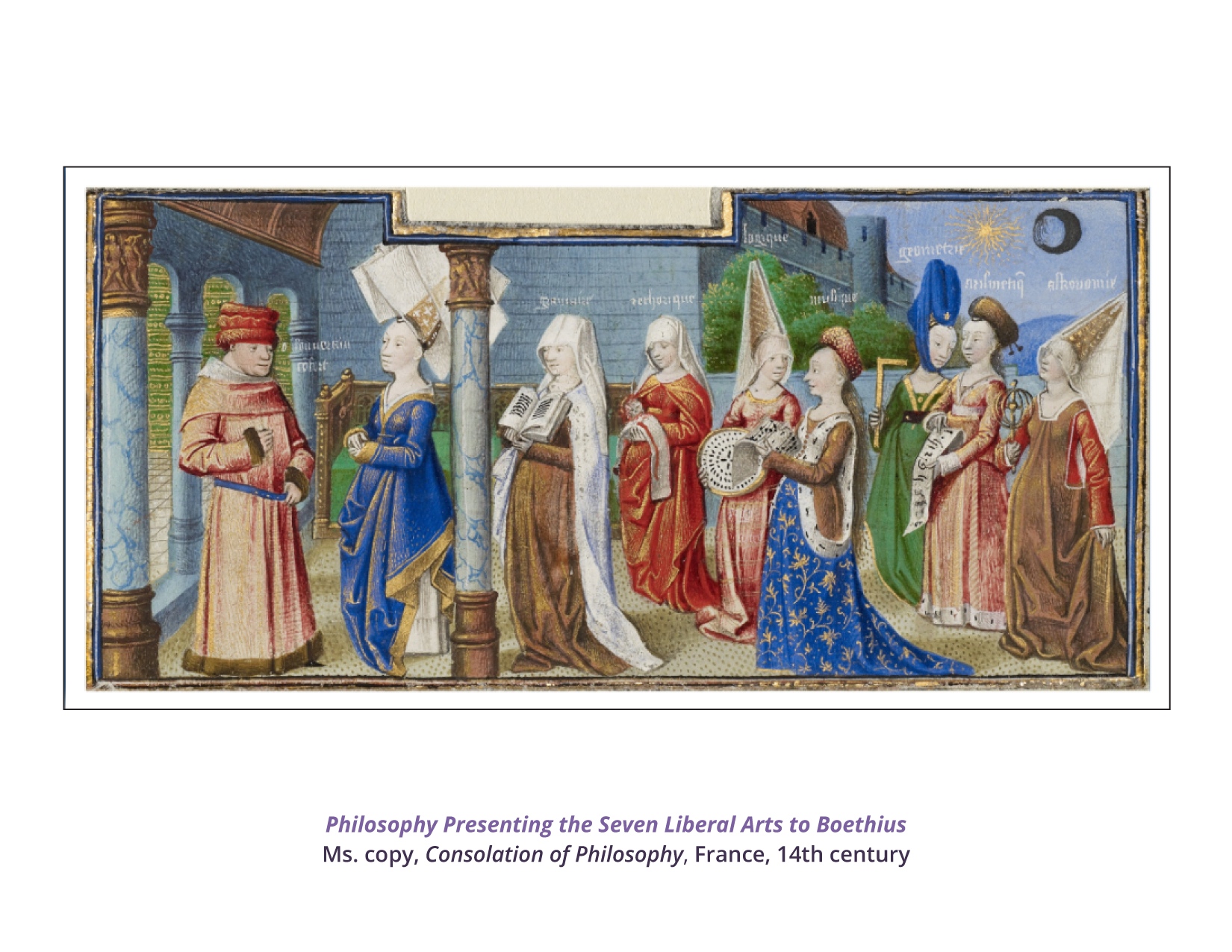

The seven Liberal Arts appear in this beautifully illustrated late medieval German medical/astrological manuscript, demonstrating the link between the seven “liberating” paths of wisdom and a healthy, happy life. The sympathetic connection existing between humanity and the stars was a commonplace of Renaissance culture, and so it is no surprise that the seven Liberal Arts are seen here paired with the traditional seven planets, their associated metals, and corresponding days of the week. Left to right: Geometry (Saturn/lead/Saturday); Logic (Jupiter/tin/Thursday); Arithmetic (Mars/iron/Tuesday); Grammar (Sun/gold/Sunday); Music (Venus/copper/Friday); Astronomy (Mercury/quicksilver/Wednesday); Rhetoric (Moon/silver/Monday).

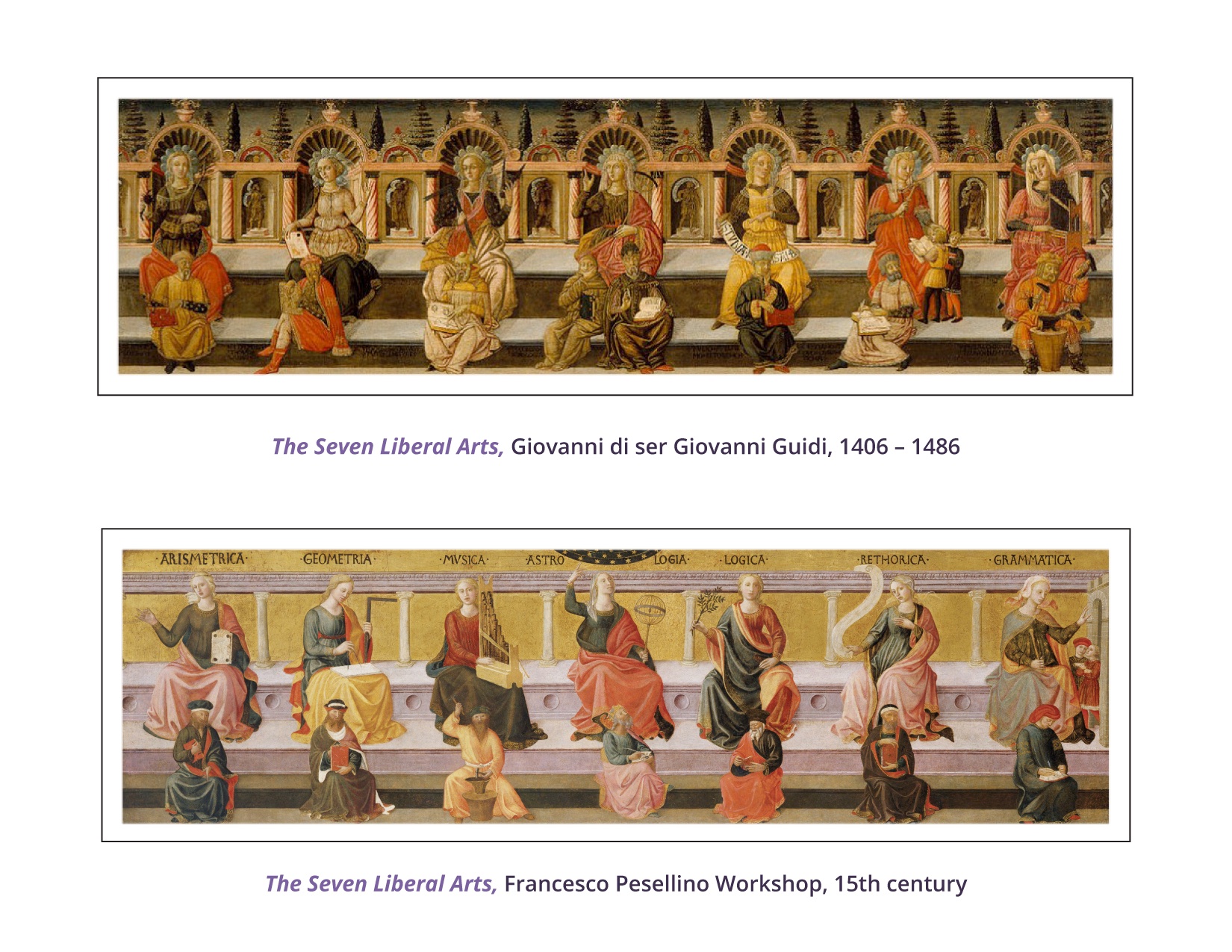

The Arts of the trivium (Grammar, Rhetoric, Logic) and the quadrivium (Arithmetic, Geometry, Music, Astronomy) are commonly depicted in groups and allegorized as women carrying identifying attributes. The Arts may also appear paired with a famous scholar associated with the practice of that Art. The attributes assigned to each Art, the order in which they appear, and the names of the accompanying scholars vary from historical period to historical period, and these changes tell us much about the preferences of the artist, his patron, and each era’s understanding of the Liberal Arts as part of daily life.

This 15th century Florentine illustration from the workshop of Francesco di Stefano Pesellino (1422-1457), for example, upholds the traditional separation of the trivium from the quadrivium, presenting the seven Arts as follows (left to right): Arithmetic (counting tablet/Pythagoras); Geometry (compass and square/Euclid); Music (portative organ/Tubal Cain); *Astrology (armillary sphere/Ptolemy); Logic (laurel branch/Aristotle); Rhetoric (scroll/Cicero); Grammar (two small boys & stick/Donatus).

Giovanni Guidi’s group, however, from roughly the same time period, intermixes the Arts of the trivium and the quadrivium (left to right): Logic (laurel branch and scorpion/Aristotle); Arithmetic (abacus/Pythagoras); Geometry (compass & square/Euclid); *Astrology (Armillary sphere/Ptolemy); Rhetoric (scroll/Cicero); Grammar (two small boys & stick/Priscian); Music (portative organ/Tubal Cain). An interesting feature of Guido’s group of Liberal Arts and human practitioners is the addition of the uomini famosi (“famous men” drawn from history that were a popular topic in 15th century art). They are portrayed in the small columned niches between the Liberal Arts.

*During the Renaissance Astronomy and Astrology were sometimes interchangeable terms, both referring to the science of measuring the heavens.

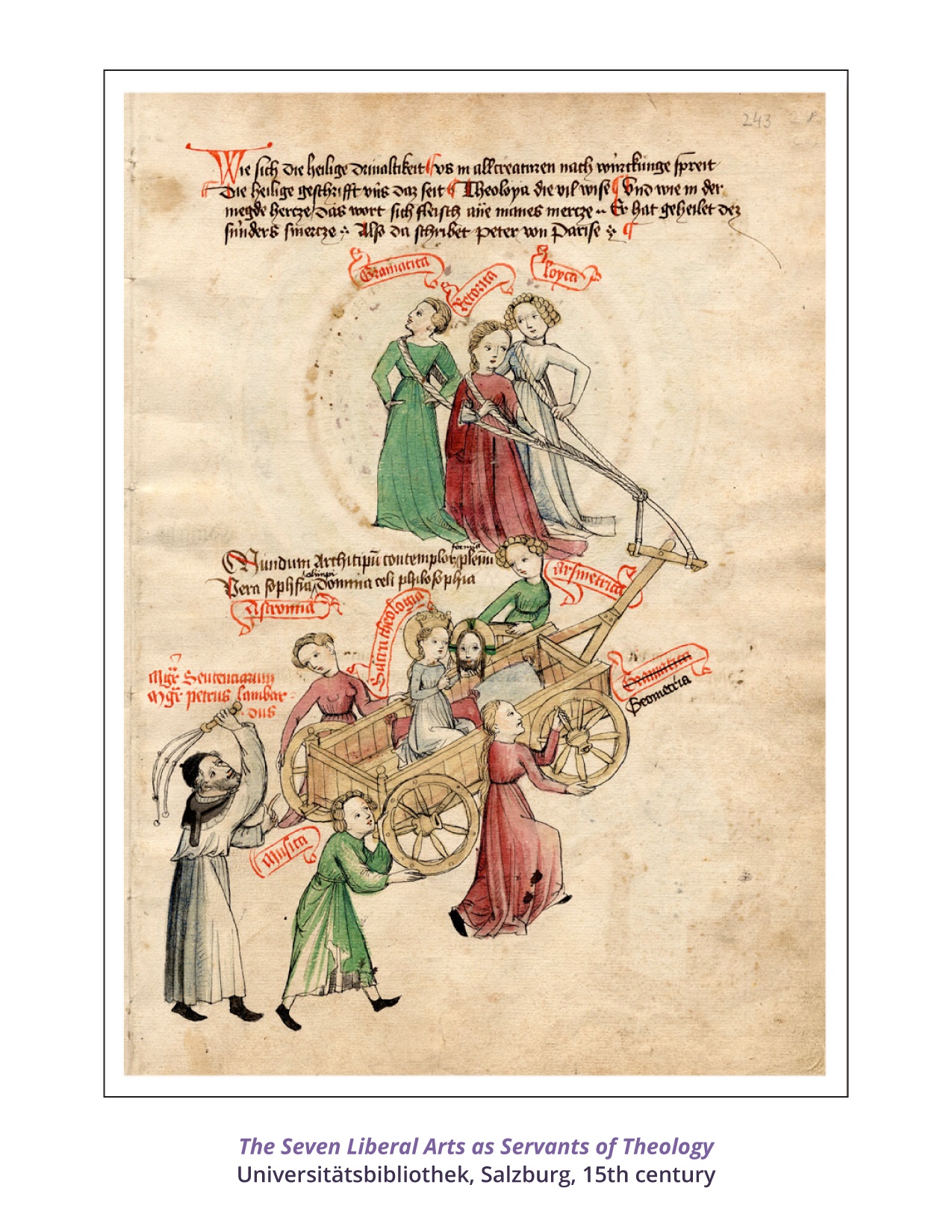

The seven Liberal Arts in this manuscript are depicted without attributes and are dressed in decidedly humble attire. They are seen here moving a heavy cart uphill, in which is seated the crowned and more elegantly attired allegorical figure of “Sacra Theologia” (Holy Theology), who holds an image of Christ. The steep hill symbolizes the difficulty of acquiring the seven paths to wisdom. The privileged position of Sacra Theologia indicates that for this artist, mastery of the Liberal Arts was little more than the means to a loftier end; that is, the study of theology. The Arts of the quadrivium (Music, Astronomy, Geometry, & Arithmetic) each turn a wheel of the cart, while the Arts of the trivium (Grammar, Rhetoric, & Logic) are yolked to the vehicle like oxen. The figure behind the cart, compelling the seven Liberal Arts forward with a whip, is identified as the medieval scholastic theologian Peter Lombard.

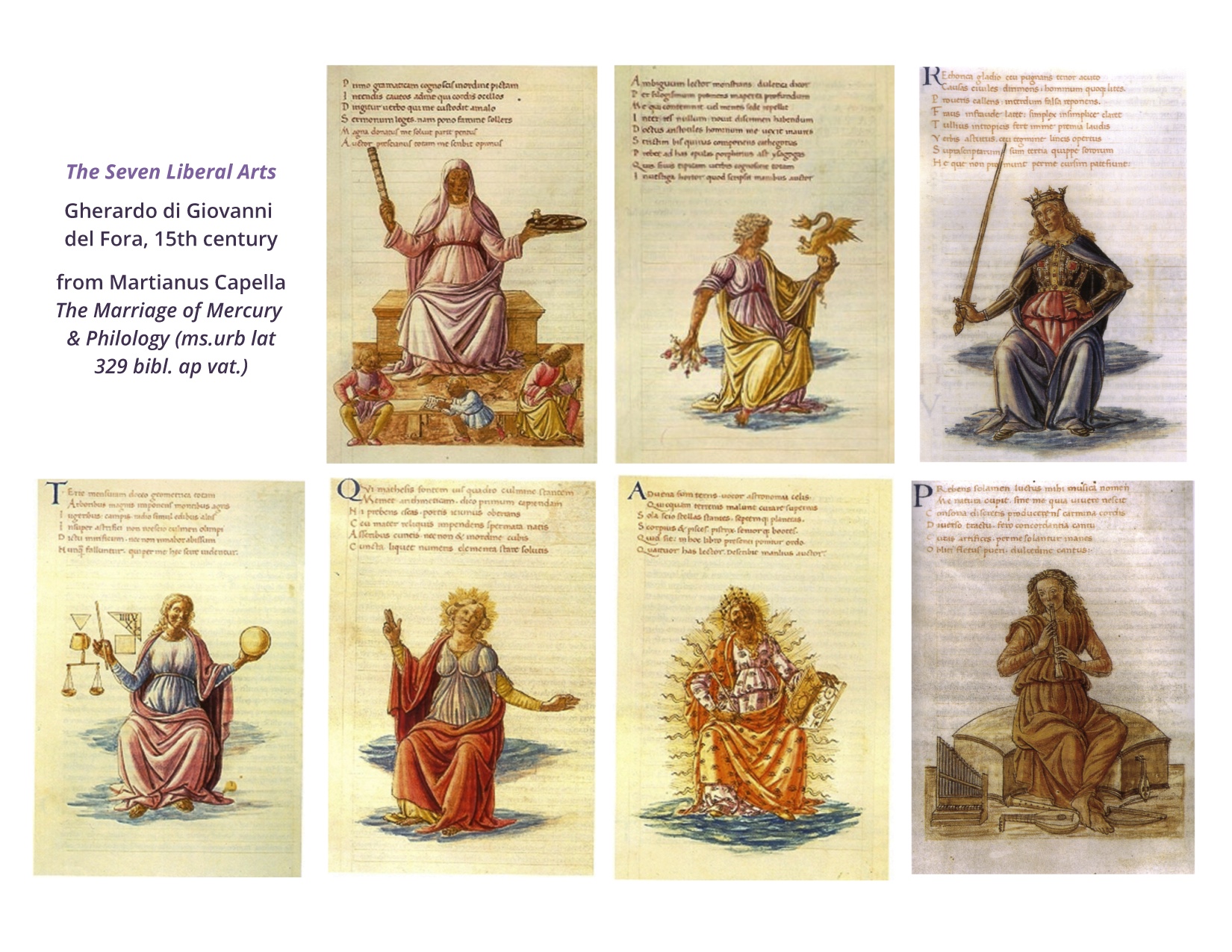

Martianus Capella’s 5th century AD De nuptiis Philologiae et Mercurii (On the Marriage of Mercury and Philology) is an elaborate narrative allegory in which the seven Liberal Arts are given as wedding gifts to the god Mercury and his human bride, Philology. Idiosyncratic though it may be, Capella’s allegory is derived from Ancient conceptions of the Liberal Arts and it remained the foundation of medieval education for centuries. In the allegory, Capella takes great care to give detailed descriptions of each Art’s dress and demeanor as she meets the assembled wedding guests. Over time, illustrations of the Liberal Arts have evolved with changing tastes and trends.

In this set of images, produced by Gherardo di Giovanni del Fora for a 15th century copy of the Marriage, we see the influence of Capella’s original descriptions as well as a few new twists. Gherardo’s Grammar is much as Capella defined her: an old woman wearing a Roman cloak, carrying a closed vessel on a plate and a golden file. Inside the vessel are tools and medicines for correcting faults of pronunciation, memory, and attention of young children; the file cleaned their teeth and tongues to clarify speech. Capella describes Dialectic (Logic) as a sharp-eyed young woman with an intricate set of braids and curls wound around her head, thick and brutish hair on her arms, and a habit of saying things no one can understand. She wears an Athenian cloak, has a serpent on her left arm, and on her right she carries a set of wax patterns held in place by a hook. Anyone taking up one of the patterns (that is, a pattern of logical argument) would be caught on the hook and drawn in to be crushed in the coils of the snake. Gherardo has preserved Logic’s cloak, curls, and hairy arms, but the snake has become a dragon, the patterns are gone, and the hooks appear attached to her fingers.

Of all the Arts of the trivium, Capella’s Rhetoric has the most regal appearance. She is tall and beautiful, carries herself with great assurance and wears a helmet, armor, and sword. She is possessed of a rich and persuasive voice, her sword and armor both attack and defend conflicting opinions. Her multi-colored Latin style cloak is decorated with all the figures of speech known to man and her belt is adorned with the rarest jewels. As we can see, Gherardo’s image comes close to Capella’s description, although Rhetoric’s helmet has been replaced by a crown and the figures of speech do not appear on the cloak.

Geometry is the first of Capella’s quadrivium Arts, and he describes her as a distinguished lady carrying a geometer’s rod in her right hand and a solid globe in her left. The sky-colored peplos draped from her shoulder is decorated with stars, lines, and intersections. On her feet are the remains of walking shoes, which she has worn to shreds while traversing the world to measure it. Gherardo has made no attempt to represent the ruined shoes, and the symbols from her cloak now appear floating in space around her image. Arithmetic in Capella’s Marriage presents an awesome appearance, with strange rays of light emanating from her forehead that she multiplies and divides at will. Her fingers are in constant motion as she counts, and her outer robe conceals the operations of nature recorded discreetly on her undergarment. Gherardo faithfully transmits the rays of light and the counting fingers.

Of all the Arts, Astronomy makes the most spectacular entrance in Capella’s Marriage, appearing out of a glowing orb that settles among the wedding guests. The orb is decked with flashing lights and Astronomy’s robe, hair, and brow shine with jewels. She holds a sextant, a book of calculations, and wears a set of golden wings. Gherardo’s Astronomy omits the wings and orb but manages nonetheless to convey her startling appearance. Capella’s Harmony (Gherardo’s Music) is perhaps the most altered of the Liberal Arts. In the Marriage her connection to musica mundana (the Harmony of the Spheres, or unsounded music) is emphasized in her physical description. Her stiff golden robe tinkles with each carefully measured movement of her body and her shield bears a series of encompassing circles (the planetary spheres), each one attuned to a musical mode. She carries miniature golden musical instruments, the sounds of which emanate not from the instruments themselves but from the planetary rings on her shield. Although Gherardo does give Musica’s simple dress a golden hue, he makes no other attempt to convey the Ancient tradition of music as a cosmic force that is so present in Capella’s description of Harmony. Instead, Gherardo’s Musica looks more like one of Apollo’s Muses, humbly demonstrating the audible, earthbound sounds of wind, keyboard, and string instruments. Her relative simplicity reflects a shift in the understanding of Music as a Liberal Art that took place during the Renaissance.

From Antiquity up to the mid-fifteenth century, “Music” was understood in two ways; as the sounded harmony created by voices and instruments which was perceived via the ears (musica instrumentalis), and also the unsounded harmony created by the heavenly spheres which was perceived via the soul (musica mundana). As the Renaissance progressed, however, the Liberal Art of Music’s connection to the Harmony of the Spheres became largely a poetic conceit and emphasis was placed more on the audible Fine Art that is the only definition of music we accept today.

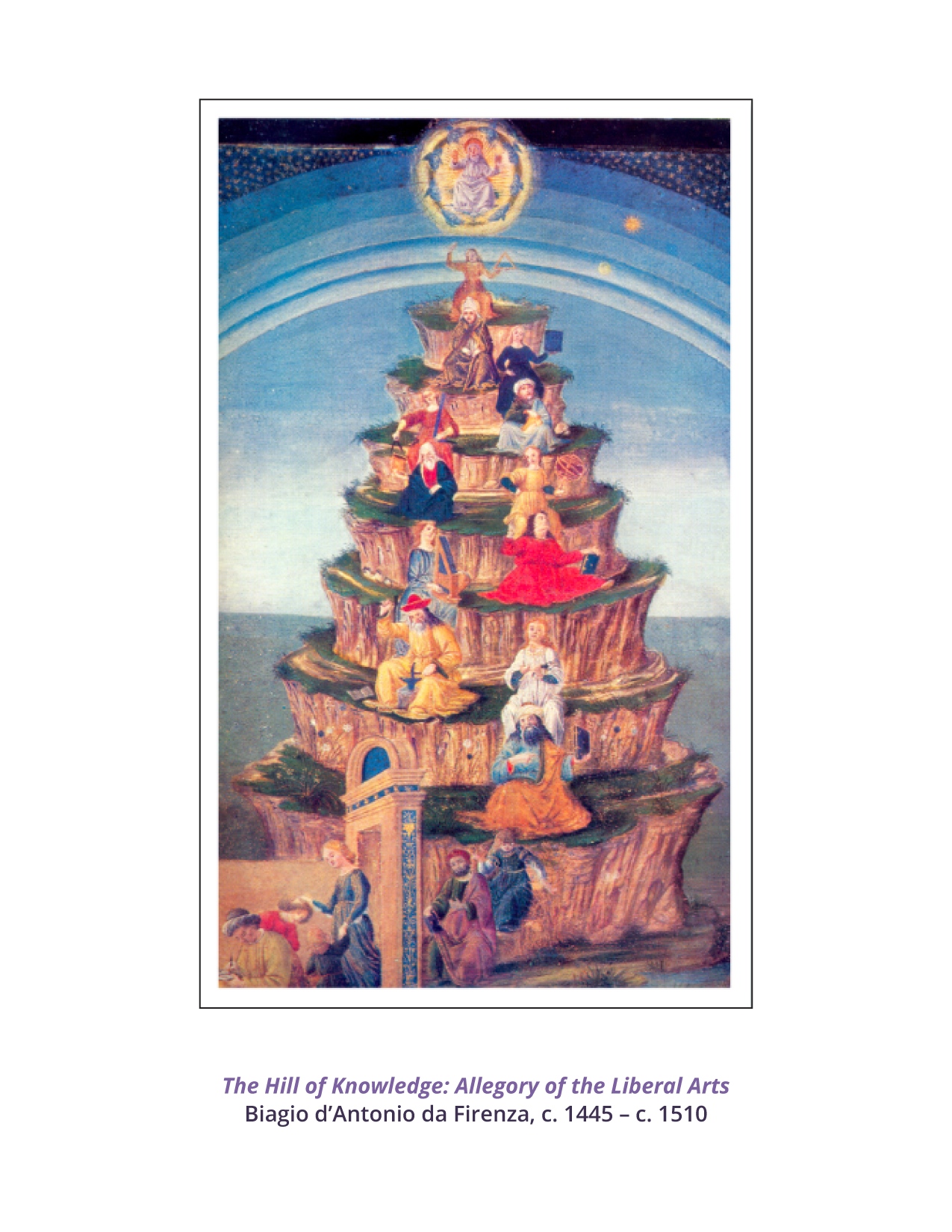

This Florentine miniature situates the female personifications of the Seven Liberal Arts on an ascending mountain path. The arrangement emphasizes that mastery of the Liberal Arts is hard work; students must climb a steep hill in order to reach the summit of all knowledge. At this point in history, the goal of the Liberal Arts was preparation for the study of theology, and it is the allegorical figure of Theology we see here on the mountaintop against a background of the planetary spheres and pointing up toward God. Below her, each of the seven Liberal Arts appears with her identifying attribute and a historical figure famous for the practice of her Art.

At the gateway to the mountain is Grammar accompanied by the Roman Grammarian Donatus (4th century AD). With them are the two small boys that often serve as Grammar’s attribute. Next is Arithmetic, counting the reeds along the mountainside and accompanied by Pythagoras (6th century BC). Logic follows, holding a scorpion and accompanied by the philosopher Zeno (5th century BC). After Logic comes Music, with a small organ on her lap and accompanied by the biblical musician Tubal Cain, who is sounding perfect harmonic proportions on his anvil (Genesis 4:22). Astronomy follows Music, holding an Armillary sphere and accompanied by the ancient Alexandrian astronomer, Ptolemy (2nd century AD). After Astronomy comes Geometry, who holds a compass and is accompanied by Euclid (4th century BC). Rhetoric is next, holding a book and gesturing as though she is making a speech. With her is the Roman orator Cicero (1st century BC). Theology is seated at the summit of the mountain, wearing a gold dress and holding a symbol of the Trinity. She is accompanied by St. Thomas Aquinas.

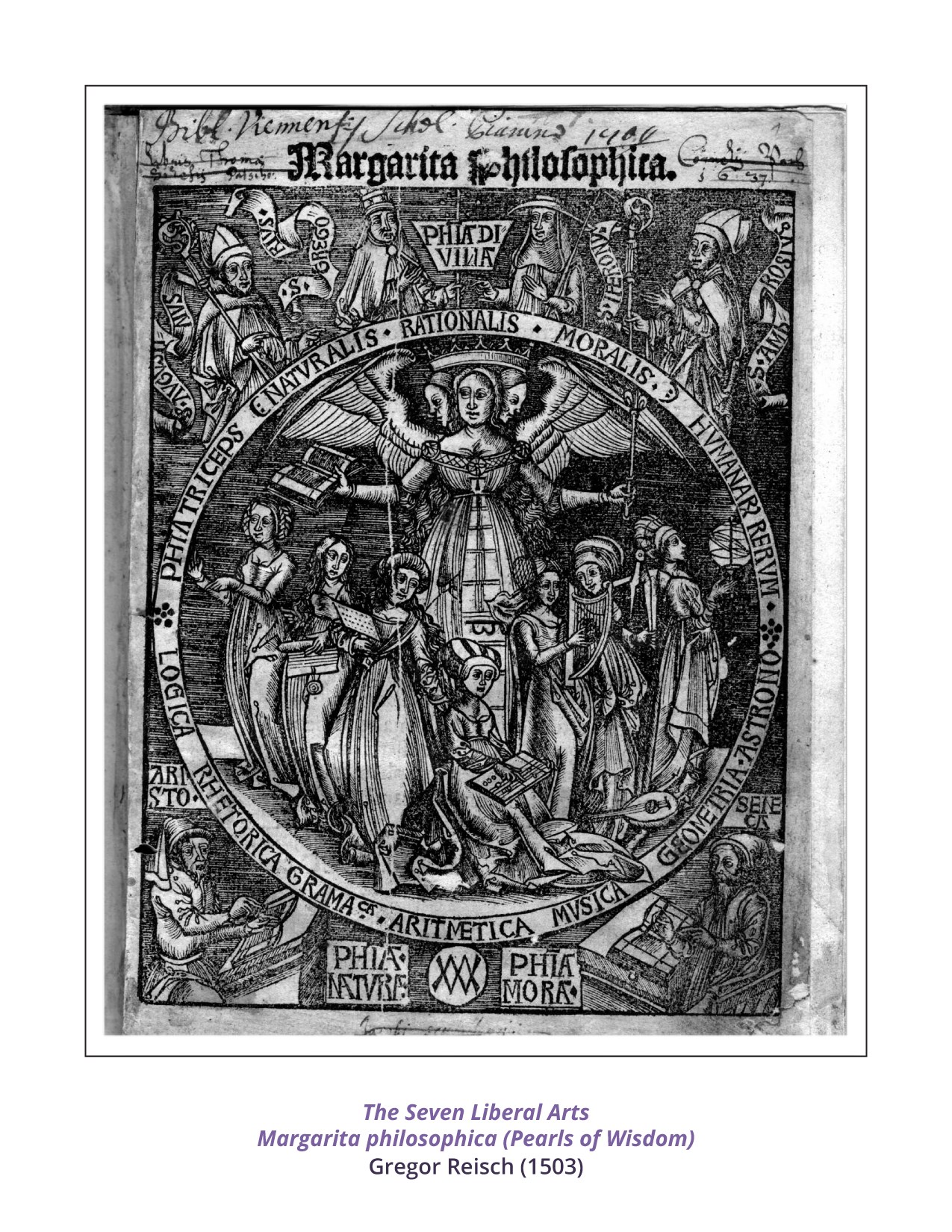

The seven Liberal Arts grace the title page of Gregor Reisch’s Margarita philosophica (Pearls of Wisdom), a popular university textbook from the early 16th century. This illustration emphasizes the Liberal Arts as the way to mastering the “triple philosophy of human affairs.” Within the circle are the seven allegorical Arts with their attributes, watched over by the winged, triple-headed figure of Wisdom. Her open book and scepter suggest the relationship between knowledge and power in earthy matters. The panel on the front of her dress depicts a ladder rising up out of the seven Liberal Arts. The Greek letter Pi at the bottom of the ladder represents practical philosophy (secular knowledge) and the Greek letter Theta at the top represents theoretical philosophy (divine knowledge).

Outside the circle are historical figures who exemplify the three types of Wisdom. On the lower left of the page is Aristotle, famous for his knowledge of natural philosophy (i.e., observation of the natural world, or “science”). On the right is Seneca, associated with moral philosophy (i.e., observation of human motivations and behavior, or “ethics”). Above the circle are the four fathers of the Church (St. Augustine, St. Gregory, St. Jerome, and St. Ambros), representing divine/rational philosophy (i.e., contemplation of the divine, or “theology”). In this image, the Arts of the trivium are mislabeled. Grammar is on the far left, Rhetoric is next to Arithmetic, and Logic is between them.

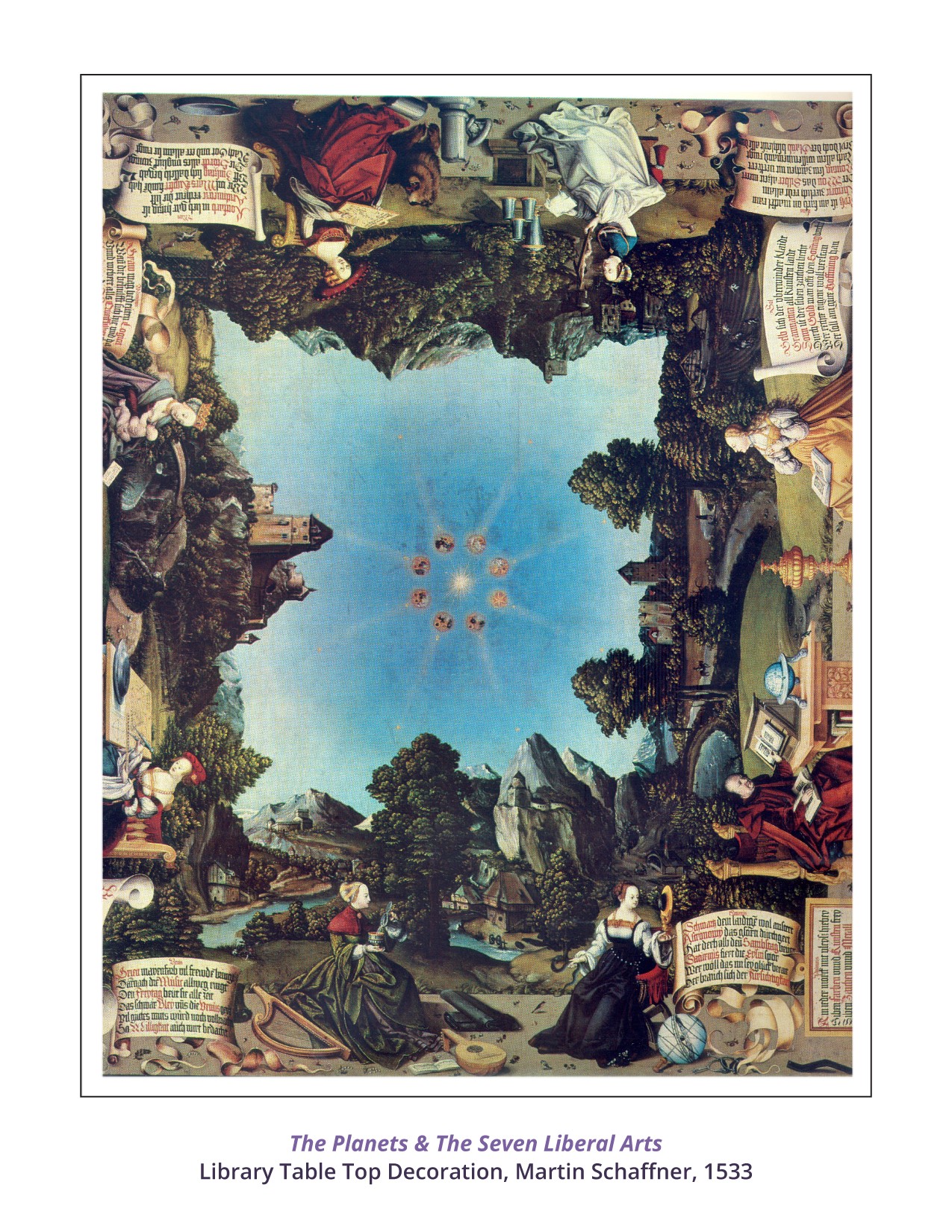

This elaborate Renaissance illustration of the Liberal Arts (Germany, 1533) is painted on the surface of a library table. The scholar who commissioned it appears in one corner (seated at his desk, reading, with his dog at his feet). Allegorical female figures of the seven Liberal Arts surround him, inspiring him and guiding him in his work. Renaissance humanism’s faith in cosmic harmony and sympathetic magic govern the details of this complex painting. The short poem on the scroll accompanying each of the female figures explains her correspondence to a planet, a day of the week, a metal, a color, and a virtue. The seven planets (and a single star representing the sphere of the fixed stars) appear in the center of the image arranged around the blazing star of Divine Intellect. Each planet extends its essence down to one of the seven Arts in a ray of light.

The message of the table top is clear: through contemplation of the Liberal Arts a scholar internalizes the planetary virtues and is thereby brought back to the source of all wisdom. Grammar (Sun, Sunday, gold, yellow, hope); Rhetoric (Moon, Monday, silver, white, faith); Arithmetic (Mars, Tuesday, copper, red, strength); Logic (Mercury, Wednesday, quicksilver, grey, love); Geometry (Jupiter, Thursday, tin, blue, justice); Music (Venus, Friday, lead, green, holiness); Astronomy (Saturn, Saturday, iron, black, prudence). Note that the planets do not appear here in their traditional order, and the metals usually associated with Mars and Venus are reversed. The distinction between the Arts of the trivium and the quadrivium is also ignored.

This set of alleged “Tarot” cards were never intended to be used for playing the European card game known as Tarot (Tarok, Tarocchi), nor were they conceived as a form of popular divination. Rather, the series of engraved images served as a teaching tool for upper class children, illustrating the organization of the Cosmos according to a distinctly Neoplatonic/Hermetic view. The 50 cards are divided into five sets of ten emblematic figures, each decade illustrating a different “order” in the Universe.

The first contains the archetypal stations of mankind (from beggar to Pope), inviting contemplation of the social role into which each embodied soul is born. The second contains the nine Muses and Apollo, emphasizing their ability to inspire the soul to return to the Source through imitative music and poetry. The third, which includes the seven Liberal Arts, teaches that the “inspiration” of the second decade must be transformed via hard work at the next stage since mastery of the Liberal Arts opens the door to even higher levels of wisdom. The fourth decade features the spirits of Light, Time, and the Cosmos plus the seven Cardinal Virtues, teaching that knowledge without character and honor has no value. Finally, the fifth decade illustrates the eight Heavenly Spheres, the “Prime Mover” and the “First Cause”, bringing the student into contact with the planetary archetypes that embody various aspects of divine wisdom.

Most of the attributes and costume details seen in the Mantegna Tarot’s trivium images come directly from descriptions of the Arts as they were first created by Martianus Capella in his 5th century AD The Marriage of Mercury and Philology (see above). There is one substantial difference, however. The Tarot’s Geometry does not only ignore the tattered shoes Capella describes; it goes so far as to completely eliminate her feet. Here, Geometry floats above the earth that it is her task to measure.

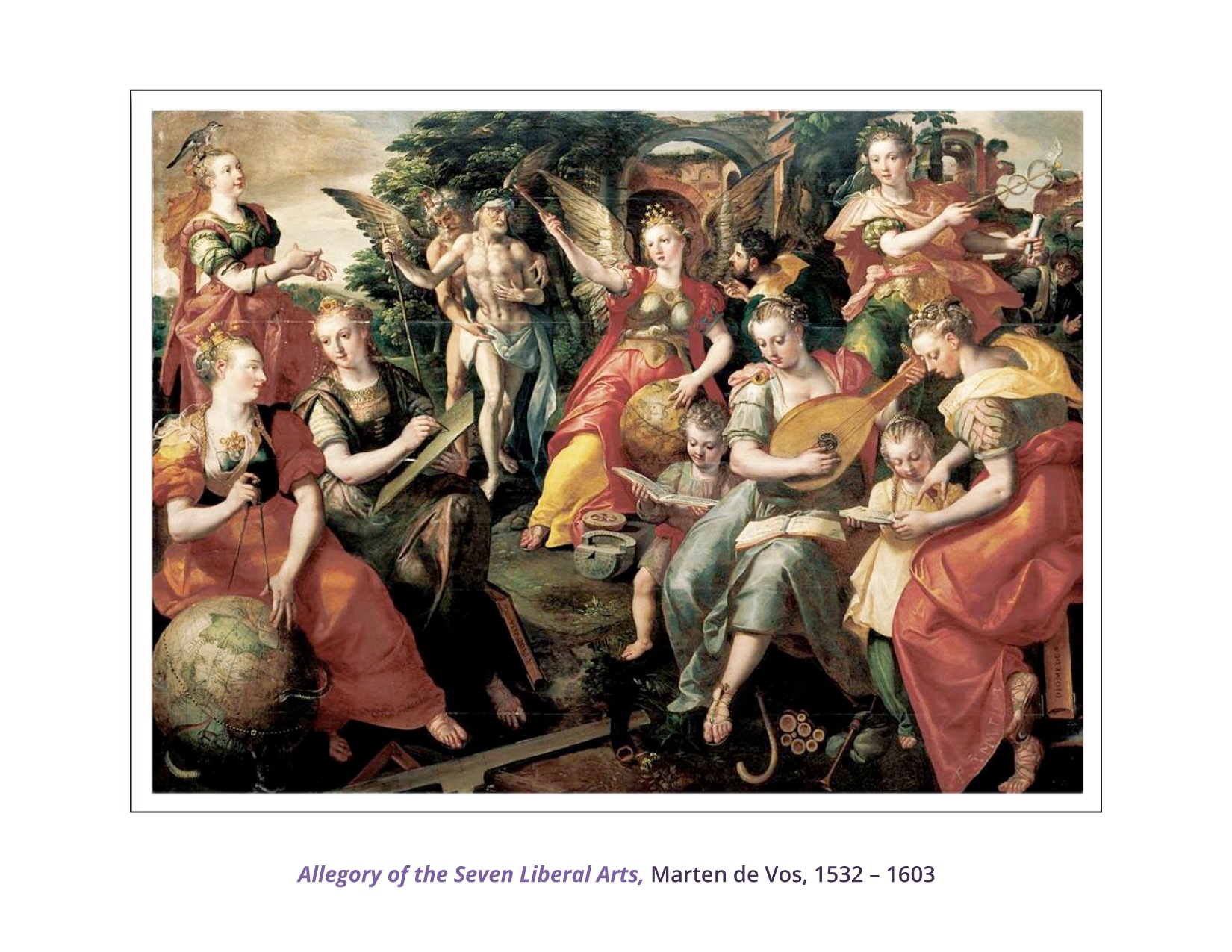

The message of this late 16th century Flemish allegory is far from clear, but informed speculation is nonetheless possible. The seven Arts of the trivium and quadrivium appear intermixed in this pseudo-classical landscape, with Geometry, Arithmetic, and Logic forming a triad on the left side of the canvas while Music, Grammar, and Rhetoric form another triad on the right. The placement of the winged Astronomy in the center of the image seems to suggest the artist’s view that contemplation of the Cosmos must be the highest goal of the Liberal Arts. To that end, he has adjusted the traditional trivium/quadrivium configuration of the other Arts to feature the rational methods of the sciences on the one hand (Logic, Geometry, Arithmetic) and the expressive methods of the humanities on the other (Rhetoric, Grammar, and Music).

The remaining figures in the painting are not part of the tradition of Liberal Arts illustration, but they may provide the key to this reconfiguration of the Arts and to the painting’s hidden message. Two of them are allegorical, but three are human insertions into an otherwise exclusively mythical landscape. On Astronomy’s right, behind the arm she extends over the realm of the rational arts and upward toward the heavens (in the typically hermetic “as above” gesture), stands a winged and bearded figure with an hourglass as a crown. He is certainly Kronos, leader of the Titans and father of the Olympian Gods. Standing in front of him is his son Zeus, patron deity of the seven Liberal Arts, depicted with his characteristic laurel wreath, beard, and spear. On Astronomy’s left, beside the arm she extends downward into the triad of the expressive arts (the hermetic “so below”), a young, hatless human being (possibly a self-portrait of the artist?) appears to be asking her an important question.

On the far right, lurking behind Rhetoric are two more human figures, one of whom rests his right hand above the hilt of his sword while seeming to contemplate grasping Rhetoric’s powerful caduceus with the other. The meaning of these extra figures might be explained by the cloth Kronos holds decorously in front of Zeus’s naked body. Its placement is certainly reminiscent of one aspect of their personal history, Zeus having castrated Kronos in order to free his siblings from their father’s oppression. But the cloth also hides the condition of Zeus’s own body; we cannot tell whether he is intact or whether, like his father, he too has been castrated.

Taken together, the presence of a fleeing human swordsman, Kronos’s attitude of tender sympathy, and a hint of crimson between Zeus’s thighs suggests the latter interpretation. As above, so below. Just as Zeus castrated his father and established a new order in the Classical heaven of Mt. Olympus, so did humanity, in the late Renaissance, sever its ties to the past by establishing a new earthly order that redefined the Liberal Arts and claimed the divine knowledge and wisdom of the caduceus for its own.