THEIR LIFE'S WORK

Brutally Honest

Bringing attention to disadvantaged people and projects

by Robin Flanigan

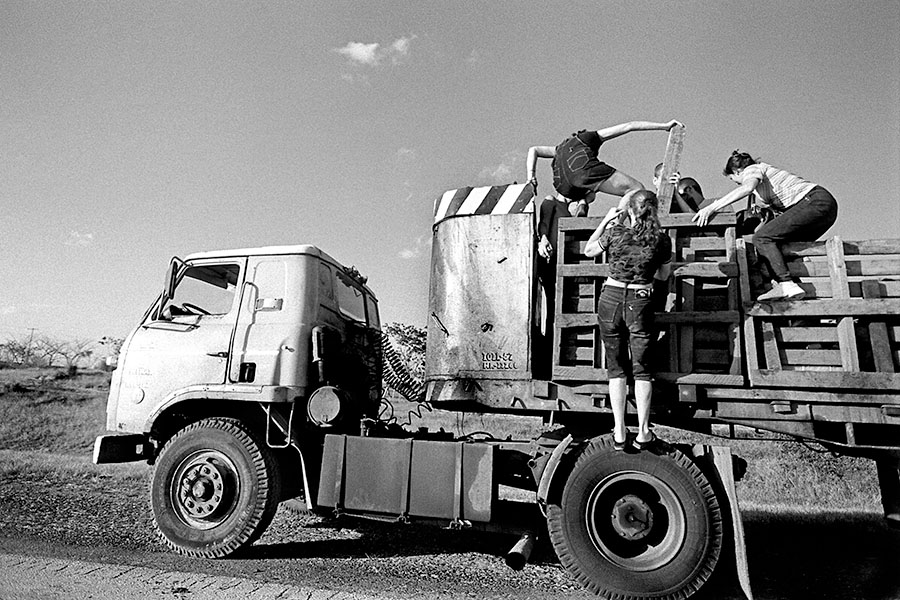

For Cubans, camiones (dump trucks) are an economical way of traveling within and between provinces. Drivers pick up passengers along their scheduled business routes for a few extra Cuban pesos.

It's hard to picture how Manuel Rivera-Ortiz ’95 grew up — the oldest of 10, living in a corrugated tin shack with dirt floors in Puerto Rico. His mother was treated as a second-class citizen in what was then a male-dominated society.

Today, Rivera-Ortiz is a documentary photographer who uses that upbringing to inform his portraits. Best known for capturing people's lives in less-developed nations, his work — which one reviewer called "brutally honest" — is in permanent collections, including the George Eastman Museum, the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art in Kansas City, and other galleries and private and corporate collections.

"I didn't set out to do this for notice," he says from his home in Rochester. "I took the pictures because I understood them, the people in them. I was there. I bring that distaste for how we can leave some people behind and not others, and how victims get pushed to the side.”

“Most people run away from the past,” he adds. “I've spent my present running into my past."

Rivera-Ortiz, who divides his time between France, Switzerland, and Rochester, focuses on humanitarian issues often ignored by mainstream media. His photography appears in five books, including his solo projects Cuba: Finding Home (Kehrer, 2021) and India: A Celebration of Life (Kehrer, 2015), as well as Voices in First Person: Reflections On Latino Identity (Simon & Schuster, 2008).

In 2010, Rivera-Ortiz established The Manuel Rivera-Ortiz Foundation, in Arles, France, as a stand-alone museum of documentary work from around the world. Its mission is to spotlight vulnerable and disadvantaged documentary projects.

"Who better to do it?" he says. "We need to document it — this history that's inclusive and honest, no matter how raw and sad it is."

Setting up the Foundation in a centuries-old building was a challenge. “Everything needed fixing or re-fixing, including electrical. Doing shows is not cheap either!" Still, Rivera-Ortiz appreciates that he's in charge; he disdains corporate naming rights. "I do what is important for me to do."

Even as an English major at Nazareth College, Rivera-Ortiz liked doing things his way. He turned in a 152-page thesis, instead of the requested 17. "I’m ready to break the rules, and I was told it was OK. I will always love Nazareth for that …”

"And I grew, and I never looked back, going all the way to Columbia University and working at magazines in Manhattan."

Laura Noble, the director of L A Noble Gallery in London, once curated an exhibition at Rivera-Ortiz's foundation. She says the two bonded over their mutual dismay about privilege in the art world, and she appreciates that he supported a diverse group of artists long before it was common to do so.

"He bucks the traditions of a lot of European practices in that way," she says. "There aren't any barriers concerning gender, ethnicity, sex, or background. What's interesting and important is the work. It's photography with substance, not just style."

For Rivera-Ortiz, his purpose reaches back to his childhood.

"I'm doing this for little boys on dirt roads who have only one pair of shoes,” he says. "As documentarians, we do these pictures because we have to. When we don't confront our demons, we can't fix even ourselves."

Robin Flanigan is a writer in Rochester, New York. Photos by Manuel Rivera-Ortiz, from his book Cuba: Finding Home.

Sisters at the family farm, with (from left) mother with baby, father, and uncle. Cuba's Vuelta Abajo region — Pinar del Rio — produces the world's most delicate tobacco leaves. Rain is scarce here, but the intense humidity and moderate temperatures make tobacco a prime crop.

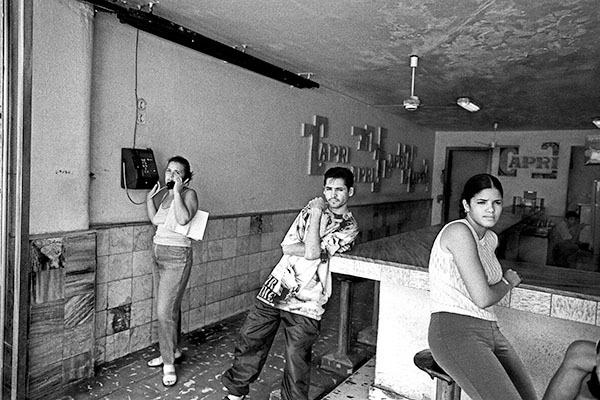

Businesses in Cuba such as this restaurant can't buy bulk because the government controls production, so they frequently have empty shelves. Yet they open daily — a psychological obligation for Cuban business owners.