THEIR LIFE'S WORK

It's All Academic

Meet three Nazareth alumni who found a higher calling in higher education.

by Sofia Tokar

David Hicks '82

Ivy-covered campuses, tweed jackets with elbow patches, whiteboards marked with shapes and scribbles—these are some of the images associated with life as a college professor.

The reality of working in academia is more complex. Faculty often balance teaching responsibilities with research, administrative work, mentoring, advising, and advocacy. Yet underpinning it all is an unabashed love of knowledge—amassing it, growing it, sharing it.

“I get jazzed by creating new courses,” says David Hicks ’82, an author, professor of English, and co-director of the Mile-High M.F.A. program at Regis University in Denver.

He recalls teaching a course on early American literature and noticing it featured only white male authors. “Emerson, Thoreau, Hawthorne, Melville, Whitman—the hall of fame,” he says. “So I started a new course on early American women writers. I wanted to introduce my students to female poets and writers of the time who need to be read, like Harriet Anne Jacobs,” the author of the slave narrative Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.

Hicks also devised classes such as Literature of the Unconscious and Epic Fails in Literature. “I just keep thinking up new ones. I learn a lot about a subject while I’m designing the course, but I also end up learning from my students when I’m teaching it.”

That insight is echoed by Lori Daggar ’09, an assistant professor of history at Ursinus College in Collegeville, Penn. “Learning from my students is one of the things I love most about working in higher education. When you’re a student, you often don’t realize you teach your professors or make them think differently.”

Daggar always wanted to be an educator, and teaching at the college level allows her to work as a historian while mentoring students. “I have a pay-it-forward mentality because I had great mentorship from the professors in Nazareth’s history department,” she explains. “I would love to do even a fraction of that for some of my students.”

Paying it forward means coming full circle for Daggar. This past winter, her students presented at a regional meeting of Phi Alpha Theta (the national honor society for history), which she attended as an undergraduate. Her junior-year independent study project formed the basis of her conference presentation and, later, part of her doctoral dissertation on agricultural mission work in Ohio and Indiana.

While Daggar went directly from graduate school to a tenure-track job, the academic career path was less straightforward for Lisa Landino ’89. “I got my Ph.D. in chemistry, but in my head all I heard was my father’s voice asking, ‘Is there any money in that?’”

Landino had tried industry work. Between her junior and senior years at Nazareth, she worked at Kodak. “The money was great, but I wore steel-toed boots to shovel chemicals and ended up getting a rash over part of my body,” she recalls. Years later, she interviewed with several pharmaceutical companies. “At one point they said to me, ‘You don’t seem like you really want to do this.’”

During her postdoctoral years, Landino realized, “I like chemistry, I can explain it well, and I’m a good scientist. Maybe it’s my calling to teach? But I enjoy working in a lab, too. And I love learning new things.”

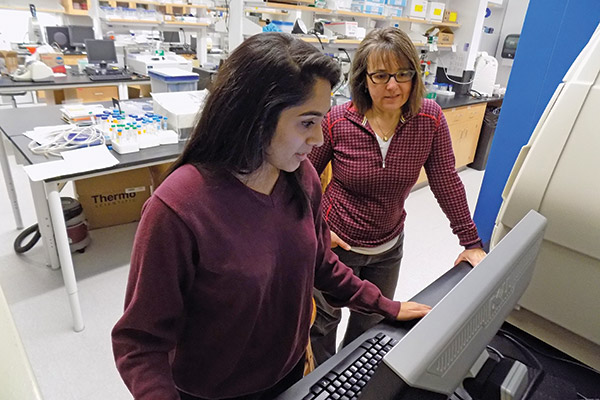

Landino eventually landed her dream job at the College of William & Mary. As a professor of chemistry, she creates and teaches classes, conducts research, trains the next generation of scientists, serves as a role model for women in science, and advocates for science students to study abroad.

“I can’t imagine anything else as rewarding,” Landino says.

Sofia Tokar is a writer in Rochester, New York.

Lori Daggar '09

Lisa Landino '89