The Portraits of Ladies

by Robin L. Flanigan

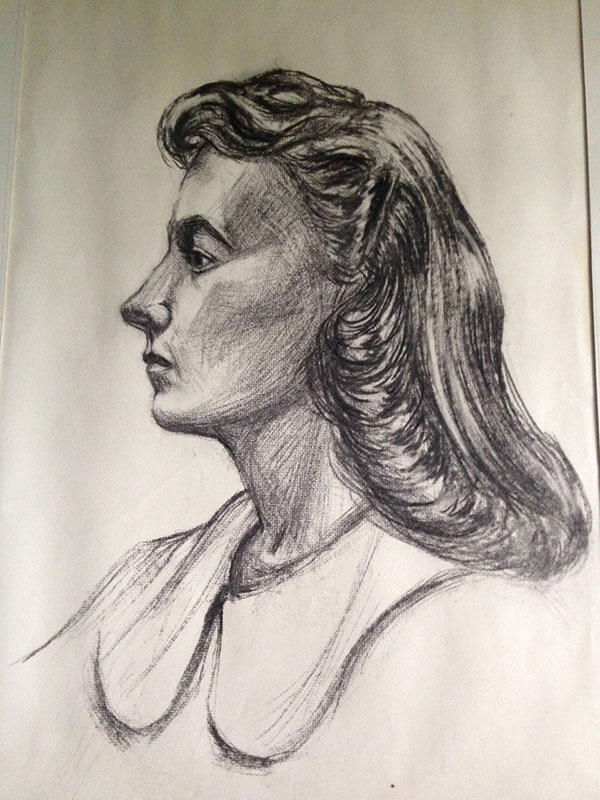

Ellen Kiley Keough '51

Mary Hope Morsch '48

Elizabeth Ann Murphy '48

Cleaning out the attic of a deceased loved one will often yield long-lost treasures. But for Ellen Murphy, the attic of her childhood home produced a mystery as well: A decrepit cardboard portfolio containing five charcoal sketches. All were of women. All dated back to October 1947. All were made by her mother, Mary Betty Keegan Murphy ’48, an art major. And none of them had a name.

Murphy recognized only one, an aunt on her father’s side. Who were the others?

“It was a complete mystery,” recalls Murphy, who resides in Mission Hills, Kansas. “But I grew up as a Nancy Drew wannabe, so this was right up my alley.”

The next couple of months turned into a scavenger hunt to find the women’s families in the hopes of offering them the artwork. Murphy asked a sister to scour her mother’s Nazareth yearbook for matches. She recruited several staff members at Nazareth to track down married surnames. She searched online obituaries (“I can’t believe how many versions of Margaret, Ellen, Katie, and Claire there are in obituaries”), even wedding announcements. Her hunt ultimately led her to families in Texas and Kansas, New York and Florida.

It turned out all the women in the sketches were Nazareth grads, and four of the five women had since passed away: Mary Hope Morsch ’48 from Florida. Betty White Whalen ’48 from New York. Georgia Conner Youngblood ’48 from Texas. Ellen Kiley Keough ’51 from Kansas.

Murphy’s aunt, Elizabeth Ann (Lib) Murphy ’48, lives in North Carolina. Lib had always been unhappy about her brother’s marriage to Mary Betty, despite having been the one to introduce them, and Murphy was unsure how her aunt would react to the artwork’s discovery. But Lib’s long antipathy softened when she learned about the sketch, and she told Murphy she loved having the beautiful piece.

Receiving Mary Betty’s artwork also meant a great deal to Georgia’s son Dennis Youngblood, who was identified with help from a former classmate. When Murphy reached him by phone, he “was just really overcome and very emotional,” she says. Last year for Christmas, he shared the portrait with the rest of his siblings by making and framing copies of it as gifts for each of them.

Mary Betty worked as an occupational therapist for years while raising seven daughters, and Murphy often wonders what her mother’s life would have been like had she pursued her art further, had she not tucked away these sketches and other pieces to be forgotten.

“If I had known these were in the attic, I would’ve taken them out a long time ago,” she says. “She would’ve loved nothing more than to reach out to these people.” Nearly 70 years after they were created, Mary Betty’s sketches reached out and made those connections for her, and the families she touched with them remain grateful.

Robin L. Flanigan is a freelance writer in Rochester, New York.

Betty White Whalen '48

Georgia Conner Youngblood '48