FEATURE

The Next Digital Revolution Has Arrived

From iPad apps to blogs and digital videos, treatment technology has never been so accessible–or so innovative

by Erich Van Dussen

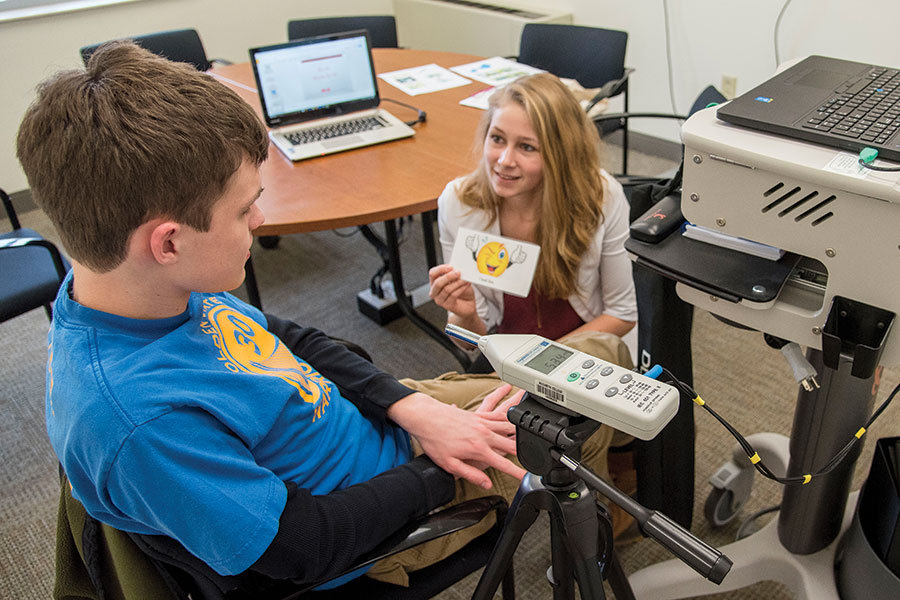

Faculty and students in the Communication Sciences and Disorders Department use technology in innovative ways to enhance client treatment.

To some, Dining With Doug may seem like just another culinary blog—a chronicle of the Italian-focused kitchen adventures of Doug Volland of Rochester. But peppered between the recipes is usually some variation on this enthusiastic declaration: “SINCE A STROKE I USE ONLY MY LEFT HAND!!!”

Volland’s blog is more than a place to find a recipe for Chicken Francese. It’s a form of brain-injury rehabilitation, and just one example of an innovative trend at Nazareth’s Communication Sciences & Disorders (CSD) Department. There, student and faculty clinicians use commonplace technology—including iPads and iPhones, consumer software, and even websites like YouTube—to help patients achieve their goals.

Technology has long been ubiquitous in therapy settings, but once upon a time the tech was notable for high price tags and never leaving the clinic. Times have definitely changed, says Heather Coles, clinical assistant professor and manager of the Neurogenic Communication and Cognition Clinic (formerly the Brain Injury Clinic) at Nazareth’s York Wellness and Rehabilitation Institute.

“Technology is an exploding toolbox today,” Coles says. “We’re finding new, creative ways to incorporate these tools into our work with clients.”

For Volland, blogging is part of a coordinated treatment array that gradually helped the stroke survivor recover functional skills as well as those associated with language and speech. Complex words like Taleggio and Bolognese are difficult for a stroke patient to utter, but they become useful motivational tools as he sounds out the recipe ingredients so they can be entered in his blog.

Technology even brings clinical benefits at Starbucks, via Volland’s directed use of an iPhone-based communication app that allows him to order complex coffee drinks without slowing down his barista. Coles encourages the use of adaptive tools to help clients build their confidence and return quickly to their normal activities. “Individuals with aphasia are faced with many discouraging situations, but resources that help them engage with the world are incredibly valuable,” she says.

From TED Talks to fantasy football

Digital advances take many therapeutic forms in clinical work at Nazareth. More specialized technology still plays an invaluable role, to be sure, but with critical differences compared to several years ago. Take the sophisticated Aphasia Scripts system—it’s no iPad app, but its PC-based accessibility speaks to modern advances in clinical tech. “Not long ago, we would have had to spend thousands or even tens of thousands of dollars to use this—not only the software, but the advanced hardware we’d need to run it,” Coles says.

Aphasia Scripts employs an onscreen speech-therapist avatar to articulate words based on highly customizable dialogue. “The conversations can be about anything,” Coles says. “For instance, for one man who’s incredibly passionate about football, we wrote a script that lets him choose players for his fantasy team.”

“Brady or Roethlisberger? Roethlisberger, Roethlisberger…” the avatar intones, using a variety of drills to tug the client into the virtual conversation by taking the words right out of his mouth.

On the opposite end of the spectrum from the complexity of Aphasia Scripts, YouTube has provided a wealth of clinical resources. Nazareth clinicians leverage YouTube’s archived TED Talks—with their encyclopedic detail about myriad topics—to help groups of clients perform project-based therapy assignments in which they take notes, summarize, and discuss a selected issue. “There’s nothing particularly clinical in a TED Talk about, say, nuclear power,” Coles says, “but the structured content makes it a useful clinical tool.”

Meanwhile, part of the undeniable appeal of working with scalable apps is the ability to create one yourself. Coles has co-developed an original piece of diagnostic technology: the iPad-based Functional Standardized Touchscreen Assessment of Cognition (FSTAC), whose hands-on user interface lets clients respond to simulated scenarios as a way of determining the severity of their condition or a suggested treatment path.

Distinct challenges, diverse solutions

Adult reactions to these therapeutic tools can vary based on their prior familiarity with personal tech, but for patients literally born in the 21st century, the comfort zone is much wider. Lisa Hiley '02, Ph.D., clinical assistant professor, and Megan Tobin, Ph.D., assistant professor, work primarily with children ages 5 to 18. “Kids’ familiarity with the technology allows us to use it really effectively,” says Hiley.

For a young girl with Down syndrome, the lingWAVES digital system generates immediate onscreen visual biofeedback that corresponds to her progress in voice and articulation therapy. “She’ll say the word ‘hap-py, hap-py’ into a calibrated microphone and the lingWAVES software shows a dolphin jump over a buoy as a way to help her monitor vocal quality,” Hiley says. “The output is simple and relatable to keep the client engaged. It’s been really effective for her and promotes progress.”

For several years, Hiley and CSD majors in the Social Communication Club At Nazareth (SCCAN) have partnered with teens at Henrietta’s Norman Howard School (NHS), which serves children with developmental disabilities as well as with the AutismUp organization to facilitate afterschool social skills groups for teens. One ongoing SCCAN/NHS project utilizes digital video as a therapeutic medium for helping NHS youth cope with challenges associated with autism and social communication disorders.

In the most recent project, inspired by TV’s Law and Order, the teens developed dramatic scenarios allowing participants to explore the importance of social rules. “They wrote the scripts and produced the videos—they’re really committed to it. It’s amazing,” Hiley says.

The SCCAN/NHS partnership is “a win-win situation,” says Rosemary Hodges, NHS director of education. “It offers our students a wonderful opportunity to interact and work together in authentic activities that promote the development of relationship building and social skills, [and] affords Nazareth students an opportunity to develop a repertoire of clinical skills they can draw upon in their future work.”

The acceleration of digital technology development over the last decade has been astounding, Hiley says. “Our clinic has a strong foundation of base technology—iPads, laptops, what have you—so when new applications come our way, we have the hardware and the connectivity we need to make it all work together.”

Coles agrees. “The tech doesn’t do it all on its own; we have to figure out how to carry it over into general use. But it’s exciting to have access to so many different tools—not only to help patients, but to help our students build a better understanding of how they will be able to work with technology in the years to come.”

Erich Van Dussen is a Rochester-based freelance writer.