LEARNING BY DOING

Treating the Whole Person

An interprofessional approach to health treatment leads to superior recovery and lets students develop real-world skills.

by Robin L. Flanigan

Having a stroke four years ago made it difficult for Ken Carpentier to retrieve the words he wanted to say — and when he was able to speak them, he wished he could articulate them better.

Carpentier began treatment at Nazareth College’s Neurogenic Communication and Cognition Clinic, where, in addition to working with speech-language pathology students, he worked with music therapy students on breath work, pacing, pitch range, and intonation.

Now he is able to converse more, and the words he produces are clearly connected. Not only that, but over time he has overcome his longstanding distaste for singing and twice has led a group of other clients in song at the end of a semester.

“It’s fun,” says Carpentier, who also receives physical therapy, occupational therapy, and art therapy at Nazareth for the stroke that affected the left side of his brain and the right side of his body. “It’s unbelievable.”

Research shows that treatment methods that engage the whole brain — rather than tackling one part of the brain at a time — lead to a more efficient recovery.

Students who use these methods, meanwhile, gain experience partnering with other disciplines before they even enter the field.

“As far as we know, we're the only college in the country that has this combination of disciplines all working together in one building,” says Music Therapy Clinical Coordinator Laurie Keough. “What we offer is different both in the sheer number of opportunities and in the intentionality of our collaborations.”

Seven major clinics — speech and language therapy, music therapy, art therapy, physical therapy, occupational therapy, nursing, and social work — serve more than 3,500 individuals and provide more than 15,000 hours of therapy and wellness services annually. Clients range from preschoolers to the elderly.

Occupational and physical therapy graduate students participate in a 10-week program with people who have developmental disabilities at the nonprofit agency Holy Childhood. The holistic approach has led to gains in cognitive, psychomotor, and affective skills, according to physical education teacher Tim Baird.

“There’s a lot of extra planning that goes into these collaborative sessions,” says Heather Coles, the adult speech and language clinic’s manager.

In activities ranging from weekly planning sessions to supervisor feedback, students are reminded consistently that this type of dynamic learning environment requires a deep understanding of — and respect for — everyone involved.

According to Katherine Saslawsky ’20, a music therapy major, this approach “creates a more well-rounded treatment for the client, but it also motivates me to be more confident in my skills because I have to educate my co-therapist about my discipline as well.”

Saslawsky recalls one of her favorite experiences: working with a woman who’d had a stroke and had spent three years undergoing unsuccessful treatment focused only on her speech. After attending speech and music therapy sessions at Nazareth, the woman began making significant progress. She started imitating sounds, and then approximating words; eventually, she could recognize whether her pronunciation was correct or incorrect.

Keough shared the woman’s joy. “We've had many tearful moments in her sessions,” she says.

Nazareth’s integrated approach takes personalized service to the next level.

Explains Olivia Krick ’20, '20G, a speech-language pathology student: “This real-world application is beneficial. Maybe I won't know exactly what's wrong with a client at first, but when I know that something is off, I feel well prepared to know who to go to in order to figure it out — together.”

Robin L. Flanigan is a writer in Rochester, N.Y.

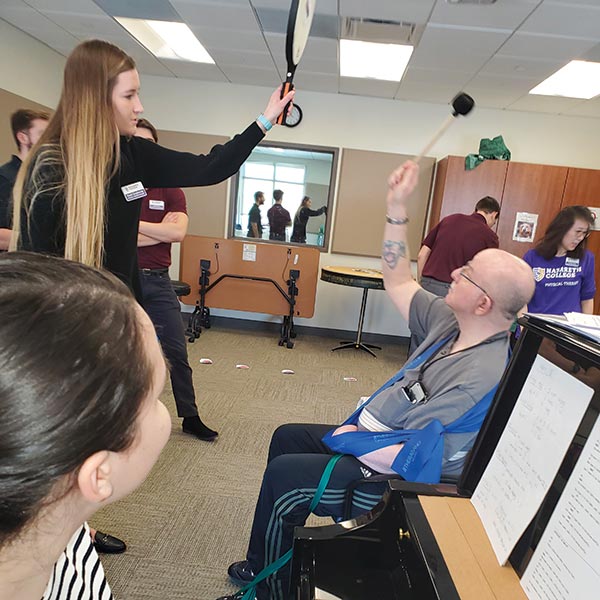

A physical therapy student (standing) provides targets for a client's reach during a range-of-motion exercise, while a music therapy student (at piano) creates an accompaniment that emphasizes the direction and force of the movement.